(Image used for Non-Profit Editorial Only)

The identity of an individual refers not only to his photographs or physical appearance but to all distinct, recognizable element which make up a particular persona, image or likeness, name, voice, signature, style, gestures, recognizable attire, look and facial features. A public persona generates an enormously lucrative and instant brand recognition among the masses.

A celebrity under Indian Laws and as well as under major legal regimes enjoys what are known as rights of publicity or image rights which enable them to commercially exploit the goodwill associated with their star and/or celebrity status.

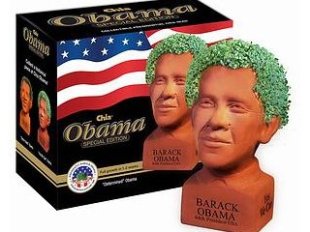

There are several ways in which the image of a celebrity can be used in advertising. The most obvious manner is tools of the trade& endorsements of products that are closely related to a celebrity’s field of activity. For instance, sportsmen routinely endorse sports equipment or clothing. Another is non-tools Endorsements where a celebrity’s image is used in connection with goods or services that are completely unrelated to his field of activity, for instance a film star endorsing a bank or a telecommunications company.

Need to protect Celebrity Rights:

The right to publicity is inheritable. Therefore descendants of celebrity can gain from the popularity created by celebrity during his/her lifetime.

Celebrity Rights are assignable &licensable for commercial benefits. In the present times publicity involves immense amount of money& the public image of a celebrity is of tremendous value. Thus, this creates an economic incentive of the public & celebrities are adequately rewarded due to their moral claim over money arising out of their name and fame.

Violation of Publicity Rights:

Use of a person’s persona for commercial gain in an unauthorized manner amounts to violation of publicity rights of the person. Any person must therefore take permission of a celebrity for using his persona for commercial gain. The unauthorized use of a celebrity’s personality can be call for an action of passing off, of unfair competition, of misrepresentation and can cause damage to their reputation. It can also amount to a breach of confidence or a violation of privacy, both duly accepted under present Indian regime.

The right of publicity encompasses the right to initiate action to prevent the wrongful appropriation of an individual’s identity for commercial purposes without his or her consent; or seek compensation.

Intellectual Property Protection in India:

- The Supreme Court of India in R.R. RajaGopal v. State of Tamil Nadu, (JT 1994 (6) SC 514) recognized right of publicity in the form of right of privacy as follows: “the first aspect of this right must be said to have been violated where, for example, a person’s name or likeness is used, without his consent, for advertising – or non-advertising – purposes or for any other matter”.

- Delhi High Court in ICC Development (International) Ltd. v. Arvee Enterprises, (2003 (26) PTC 245 Del) held that the right of publicity does not extend to events and is confined to persons.

Under Trademarks Act individuals may apply for the protection of their name, likeness among other things, with the Indian Trademarks Registry in order to obtain statutory protection against misuse. This is of strategic importance for celebrities who intend to use their image and likeness to identify their own or an authorized line of merchandise. Few of the pertinent cases are discussed below:

- In DM Entertainment v Jhaveri (Case 1147/2001), Daler Mehndi, a famous Indian composer and performer, brought an action against the defendant following the registration of the domain name ‘dalermehndi.net’. The Delhi High Court restrained the defendant from using the trademark DALER MEHNDI, thus recognizing the fact that an entertainer’s name may have trademark significance.

- Another case involving an Indian citizen was that of Ratan Tata, the chairman of Tata lodged a complaint in Word Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) arbitration panel seeking the transfer of domain names comprising the name Tata (Tata Sons Ltd v Ramadasoft (Case D2000-1713, February 8 2001)).

- Sourav Ganguly v. Tata Tea ltd., Sourav Ganguly, a hugely popular cricketer and former Indian captain, who returned from a tour of England to find a well-known brand of tea cashing in on his success by offering consumers a chance to congratulate the cricketer. The offer implied that the cricketer had associated himself with the promotion, which was not the case. Ultimately, Sourav Ganguly could successfully challenge it in the Court before settling the dispute amicably.

In a different but pertinent case, In 2009 Montblanc released luxury pens in India called “Mahatma Gandhi Limited Edition 241” and “Mahatma Gandhi Limited Edition 3000”, which were engraved with Mahatma Gandhi’s portrait on the nib. Tushar Gandhi (Gandhi’s great-grandson) had given his prior approval; however, the launch was met with immediate opposition on account of the Protection under the Emblems and Names (Prevention of improper use) Act 1950. Under this act, unless the government permits it, names and images of nationally important personalities cannot be used for any trade, business or professional purpose. As a result, Montblanc was forced to withdraw its advertisements and the pens in question from the market.

The Indian copyright Act, 1957 does not define the word “celebrity”. But reference can be made to the definition of a performer as given under section 2(qq). The performer includes an actor, singer, musician, dancer, acrobat, juggler, snake charmer, a person delivering a lecture or any other person who makes a performance. There is not much clarity as to what aspects of celebrity rights may be protected under Copyright Law.

The Indian Copyright Act, 1957 provides protection of specific image in the form of a photograph, painting or other derivative works. To pursue an action of infringement individual must show ownership of copyright in the image or photograph and copying of that image. In the context of celebrities, it becomes difficult for them to show their ownership of their specific image or photograph being exploited.

- In Titan Industries Limited v Ramkumar Jewellers ([CS(OS) 2662 of 2011]), the plaintiff had asked celebrity couple Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan to endorse and advertise its range of diamond jewellery sold under the brand name Tanishq. The couple had assigned all the rights in their personality to the plaintiff to be used in advertisements in all media, including print and video. The plaintiff had invested huge sums of money in the promotional campaign. The defendant, a jeweler dealing in identical goods to those of the plaintiff, was found to have put up a hoarding identical to the plaintiff’s, including the same photograph of the celebrity couple displayed on the plaintiff’s hoarding.Since the defendant had neither sought permission from the couple to use their photograph, nor beenauthorized to do so by the plaintiff, the court held it liable not only for infringement of the plaintiff’s copyright in the advertisement, but also for misappropriation of the couple’s personality rights. The court thereby granted an interim injunction in favour of the plaintiff while specifically recognizing the couple’s rights in their personalities.

- Phoolan devi Vs Shekar Kapoor & others, Phoolan Devi herself protested that the film has distorted the facts .She sought an injunction as she had given up her past criminal activities & had started her life afresh. The court held that issue need to be thoroughly examined and the implications of such exhibition on the private life of an individual be scrutinized before permitting release of such films. Thus, a celebrity can protect his /her name & image as a constitutional right.

Remedies:

Passing Off Action is a remedy to damages to reputation and goodwill of an individual caused by misrepresentation by another person trying to pass off his goods or business as goods or business of another .An action in passing off may lie for any unauthorized exploitation of celebrity’s goodwill or fame by falsely indicating endorsement of products by the celebrity.

An action for passing off requires proof of:

- the reputation of the individual;

- some form of misrepresentation;

- irreparable damage to the individual.

In Henderson Vs Radio Corporation the claimants were professional ballroom dancers .The defendants produced a record “strictly for dance” in which they used a picture of the claimants in the cover illustration. The claimants argued that this amounted to “Passing Off “.The court held it as wrongful appropriation of personality and professional reputation of plaintiff’s.

Provisions in International Conventions:

Few landmark conventions in regards to protection of performer’s rights are The International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations,(1961)Rome Convention, TRIPS & The WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty 1996 (WPPT) .

Conclusion:

The protection of publicity and image right is expanding in a celebrity obsessed culture of India. Recent cases where legendary Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan spoke out against the unauthorized use of a sound-alike of his distinctive deep baritone in an advertisement promoting a brand of gutka (chewing tobacco), an association which was detrimental to his image and of the famous Indian actor Rajnikanth ,published a legal notice in various magazines before the release of his latest film prohibiting anyone from damaging his screen persona or from using his character in the film for any financial gain including advertisements ,and impressions by comedians ,clearly suggests that Right of publicity has emerged as an individual class of IP protection.

While Indian celebrities have intermittently attempted to protect their personality rights, the law on this aspect has taken a long time to develop.